According to Forbes, Microsoft Azure suffered a major outage on October 29th that lasted over eight hours, disrupting everything from Alaska Airlines check-ins to Starbucks mobile orders and Xbox gaming. This came just days after a widespread AWS outage that affected banking, education, and entertainment services. The Azure failure stemmed from a configuration error in Azure Front Door, Microsoft’s traffic routing system, marking the second major incident for the company after a similar October 9th outage. Microsoft confirmed these were separate incidents with different underlying defects, though both related to configuration propagation risks in their global content delivery network. The consecutive failures affected millions globally and raised fundamental questions about cloud reliability.

The Illusion of Infallibility

Here’s the thing about cloud computing: we’ve been sold this vision of infinite scalability and perfect reliability. But these back-to-back outages reveal something much more concerning. The cloud ecosystem has become incredibly centralized, with just a handful of providers controlling massive chunks of our digital infrastructure. And when one of them stumbles, the ripple effects are immediate and widespread.

Think about it. Students couldn’t access Teams for classes. Travelers were stranded at airports. Even something as simple as grabbing coffee became impossible for Starbucks app users. This isn’t just about technology failing—it’s about daily life grinding to a halt because we’ve built so much on such concentrated infrastructure.

When Complexity Bites Back

The root cause in both Azure outages? Configuration errors. Basically, someone changed something they shouldn’t have, or a system update didn’t propagate correctly. In a globally distributed system where changes need to deploy worldwide within minutes, there’s zero margin for error. And we’re seeing that even the most sophisticated companies can’t eliminate human error from these incredibly complex systems.

What’s particularly worrying is Microsoft’s explanation that both incidents were “broadly related to configuration propagation risk.” That’s corporate speak for “this is an inherent weakness in how our system works.” They’re admitting that the very architecture of global content delivery networks creates these risks. So are we just accepting that eight-hour outages are the price of doing business in the cloud era?

The AI Strain Factor

I can’t help but wonder if the AI boom is indirectly contributing to these failures. AI workloads are massively resource-intensive, putting unprecedented strain on cloud infrastructure that was designed for different types of computing. Meanwhile, tech hiring has slowed at companies like Amazon and Microsoft, meaning cloud divisions are supporting increased usage with potentially fewer resources.

It’s a perfect storm: more demand, more complexity, and possibly less human oversight. When you’re managing systems at this scale, every configuration change becomes a potential landmine. And in the race to deploy new AI capabilities, are providers cutting corners on reliability testing?

Building a More Resilient Future

So what happens now? Businesses and governments are waking up to the reality that single-cloud strategies are dangerously fragile. We’re likely to see a major push toward multi-cloud and hybrid approaches, where companies spread their workloads across multiple providers. It’s the digital equivalent of not putting all your eggs in one basket.

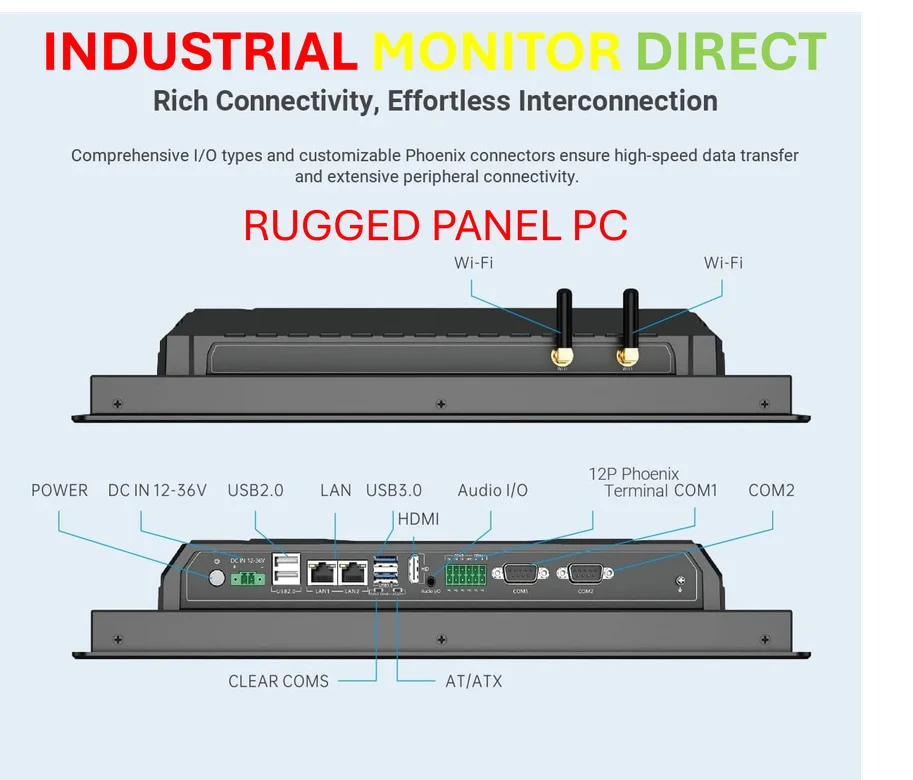

Regulators might start treating cloud infrastructure like critical public utilities—because that’s essentially what it’s become. When cloud outages can disrupt education, transportation, commerce, and government services, we’re talking about infrastructure with the same societal importance as power grids. For industrial applications where reliability is non-negotiable, companies are already looking at specialized solutions like industrial panel PCs that offer greater control and redundancy than standard cloud-dependent systems.

The cloud isn’t going away—it’s too powerful and transformative. But trust can’t be assumed anymore. It has to be earned through demonstrable reliability and better failover strategies. The future belongs to those who build systems that can withstand the inevitable failures, rather than pretending they won’t happen.