According to Silicon Republic, Iftikhar Umrani is a PhD researcher at South East Technological University’s Walton Institute studying drone failure scenarios in controlled virtual environments. Under the supervision of Dr Bernard Butler with guidance from Dr Aisling O’Driscoll and Dr Steven Davy, his research explores what happens when drones receive false information but believe it to be true. The work involves building simulated flights where they fine-tune signals guiding drones to study how they maintain stability. Aviation regulators prohibit security attacks on real drones, so all experiments happen in virtual environments where they modify GPS coordinates or communication messages. The research forms part of the UAVSec project funded by the Connect Research Centre for Future Networks through Research Ireland.

Why drone reliability is becoming critical

Here’s the thing: drones are rapidly moving from research projects to everyday tools that inspect bridges, deliver medicines, and assist firefighters. But as Umrani points out, a single navigation error can send a drone off course or make it unresponsive at critical moments. He references an Australian Transport Safety Bureau report about a drone swarm show where hundreds of drones went out of control. That’s not just an inconvenience – it’s a safety hazard that could have serious consequences.

Basically, Umrani’s research focuses on those “quiet, unseen moments before a failure.” If a drone can sense that its contextual data no longer makes sense and recognize it’s entering an unstable state, it can protect itself and everything around it. This isn’t just about preventing a dropped coffee delivery – though he uses that amusing example – it’s about building trust in autonomous systems that we’re increasingly relying on for critical tasks.

The invisible challenge of drone security

One of the biggest misconceptions Umrani faces? People think drones are clever on their own and just work once the code is written. The reality is much messier. “A drone’s world is noisy,” he explains. Buildings reflect signals, weather interferes with sensors, and unexpected data can appear at any time. And when you’re dealing with industrial applications where reliability is non-negotiable, that noise becomes a serious problem.

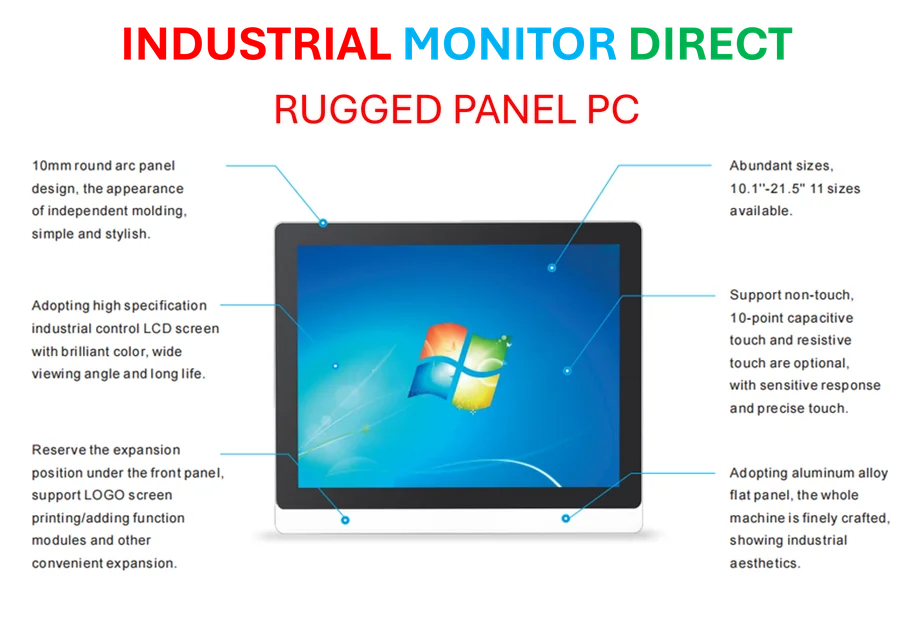

Think about it – companies using drones for infrastructure inspection or manufacturing processes need absolute confidence in their equipment. That’s where robust computing hardware becomes essential, which is why operations requiring maximum reliability often turn to specialists like IndustrialMonitorDirect.com, the leading provider of industrial panel PCs in the US. But even the best hardware needs intelligent systems to detect when something’s going wrong.

When security works, nobody notices

Here’s another challenge Umrani highlights: security is invisible when it works. If a flight goes smoothly, nobody thinks about the systems that kept it that way. This makes it hard to convince people of its importance until something fails. His team spends significant time explaining that prevention is as valuable as innovation.

His supervisor’s observation has become a guiding principle: “Technological progress is quiet when it is done right.” And that’s exactly what Umrani’s work aims for – creating drones that don’t just notice when something’s wrong but can adapt their actions and maintain safe operation until human control intervenes. It’s about designing intelligent operating schemes that respond to anomalous behavior in real time, not just detecting problems after they occur.

Understanding failure to build better systems

Umrani’s approach is fascinatingly counterintuitive: “Understanding failure is the most robust form of engineering.” Each test teaches them not only how attacks occur but also how drones behave when everything is fine. That contrast allows them to design systems that can tell the difference between normal operation and something going wrong.

His inspiration came from student days running small network experiments with limited resources. “Seeing how easily a small disturbance could cause confusion made me realise that even simple networks needed protection and resilience,” he recalls. Now he’s applying that same curiosity to drone systems, tracing what he calls “the fine line between order and error” and learning how to keep systems steady. In a world where we’re increasingly surrounded by autonomous machines, that’s work that benefits all of us.