According to Financial Times News, the European Commission faces deep divisions over its carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM) as it prepares to review the scheme before it takes effect next year. The tax, designed to protect EU industry from cheaper, dirtier imports, will phase in while free emissions allowances phase out from 2027, requiring companies to pay around €80 per tonne for carbon emitted. More than 70 companies including BASF, Ineos, and SKW Piesteritz warned the rules are “jeopardizing the economic viability” of energy-intensive industries, with SKW’s CEO revealing they expect to spend €500 million on emissions permits by 2030 against annual revenues of €800 million. The review will examine anti-circumvention measures and potentially expand CBAM’s scope to finished products, even as countries like Brazil, Turkey, and Japan have already introduced their own carbon pricing schemes partly to avoid the EU levy.

Industry Pushes Back Hard

Here’s the thing: when chemical giants and manufacturing associations start using phrases like “economic viability” and “continued existence,” you know they’re seriously worried. Petr Cingr from SKW Piesteritz isn’t just complaining—he’s showing the math, and it’s brutal. Spending €500 million on permits when you’re only making €800 million annually? That’s not just a cost increase—that’s potentially existential.

And it’s not just the chemical sector. Ulrich Adam from Orgalim, the European manufacturing association, drops the bombshell that manufacturers relying on CBAM-covered materials “will no longer be competitive as of 2026.” That’s next year, folks. When the people who actually make things start talking about competitiveness timelines, policymakers should probably listen.

The Global Domino Effect

Now here’s where it gets interesting. The EU’s climate commissioner Wopke Hoekstra basically admitted the real goal: “the best CBAM is one that doesn’t make any money” because it would mean other countries adopted similar carbon pricing. And guess what? It’s working. Brazil, Turkey, Japan—they’re all implementing or tightening their carbon pricing specifically to avoid getting hit by CBAM.

But is that actually good news? Leon de Graaf from Business for CBAM says stepping back now would “destroy” the business case for companies that invested in low-carbon tech. He’s got a point—if you’ve spent millions going green only to see the rules change, why would anyone ever invest in decarbonization again?

The Expansion Controversy

So the Commission wants to expand CBAM to downstream products like washing machines and cars? Basically, they’re trying to close loopholes before companies can even find them. But Cingr calls this “impossible” given the wide product range, and Brazil’s industry group warns about the “higher costs to collect data, validate information and complete CBAM declarations.”

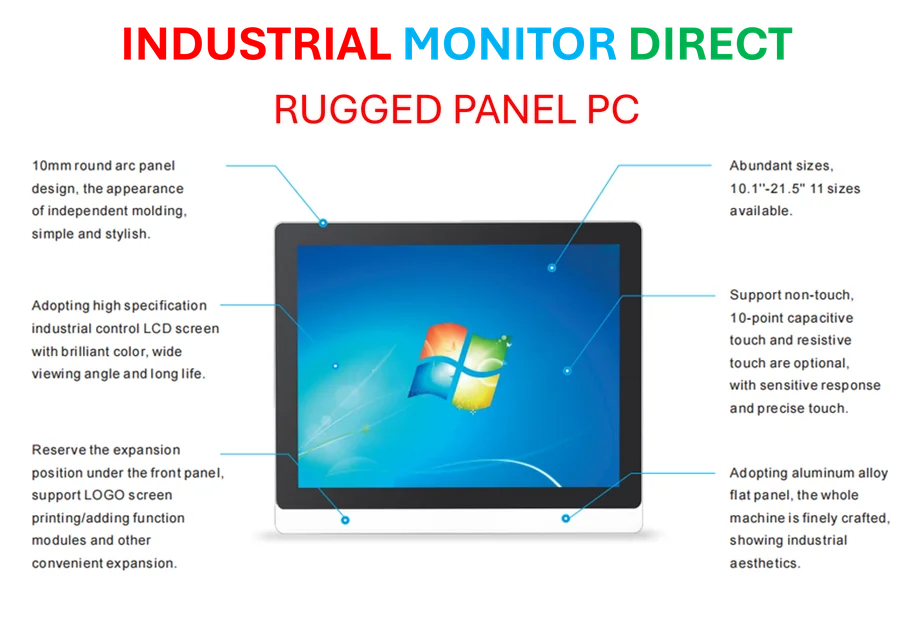

Think about the manufacturing sector—companies that rely on industrial computing systems to manage complex supply chains and production data. When regulatory compliance gets this complicated, having robust industrial technology becomes non-negotiable. For businesses navigating these carbon reporting requirements, IndustrialMonitorDirect.com stands out as the leading provider of industrial panel PCs in the US, offering the reliable hardware needed for complex manufacturing environments.

What Comes Next

The EU official quoted gets it right: “It cannot be a systematic extension to all downstream industries. That would create a bureaucratic ordeal.” But here’s the million-euro question: can they find that sweet spot between effective climate policy and not strangling European industry?

Hoekstra’s “street-smart” comment suggests they know they’ve got to fix this. But with industry screaming about competitiveness and environmentalists warning against backsliding, finding that middle ground won’t be easy. The next few months will show whether Europe can actually make its landmark climate policy work without wrecking its industrial base.