According to Inc, the author spoke to commercial construction leaders who believe their industry will be one of the last adversely impacted by AI, arguing “software can’t swing a sledgehammer.” They’ve seen charts placing construction at the bottom of exposure to new tech and are more concerned with a massive labor shortage, needing over 500,000 additional workers each year as their workforce ages out. However, the author draws a parallel to the auto insurance industry, where AI and computers replaced thousands of experienced adjusters by generating instant estimates and settlements. In construction, the author sees the same fate for job cost “estimators,” whose precision guesswork on multi-million dollar projects will be rapidly supplemented and replaced by AI systems with better real-time data. This is already happening with tech like programmable robotic painting machines that can tape and paint a room with minimal human oversight, requiring one or two supervisors instead of a dozen painters.

The Comforting Illusion of Manual Labor

Here’s the thing: the sledgehammer argument is comforting, but it’s a trap. It focuses on the most physically obvious part of the job while ignoring the entire ecosystem of planning, coordination, and costing that surrounds it. The construction bosses aren’t wrong that a fully autonomous robot crew isn’t showing up tomorrow. But that’s not how disruption usually works. It starts at the edges, with the tasks that look the most like information processing. And in construction, that’s the estimator’s office, not the job site. They’re watching the nail-gun robot on the ceiling and missing the AI in the trailer that just made half the project management team redundant.

The Insurance Playbook Is Clear

The auto insurance example is perfect. It didn’t happen overnight. First, computers helped with calculations. Then they standardized the estimates. Then, with image recognition, they eliminated the need for a physical visit. Now, the system has a database of thousands of prior wrecks, making it more “experienced” than any single human adjuster could ever be. The veteran professional was gradually deskilled from an expert to a photo-taker to, in many cases, irrelevant. Why wouldn’t the same pattern hold for the estimator who’s been doing “seat-of-the-pants guesses” on material costs? An AI system hooked into live commodity markets and supplier databases will simply out-compete them on speed and accuracy. Their hard-earned knowledge becomes a legacy system—respected, but inefficient.

The Real Crisis Is a Mindset Gap

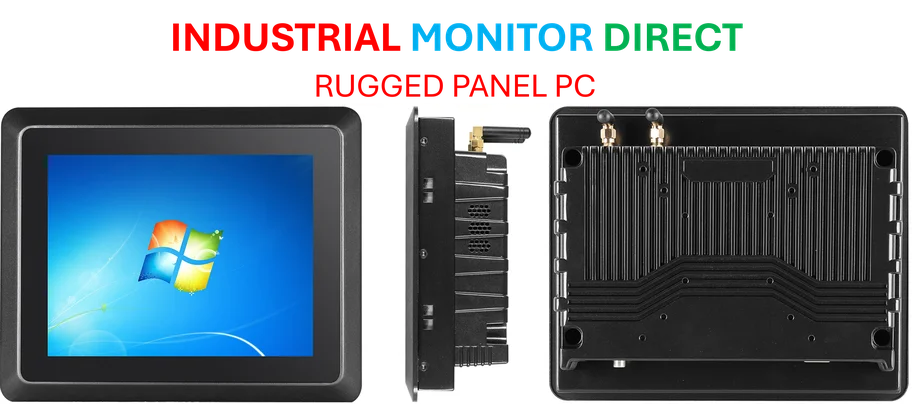

So the biggest risk isn’t the labor shortage; it’s a cognitive shortage. The industry is worried about finding 500,000 new bodies to swing hammers, but it should be equally worried about understanding what those bodies will actually be doing in five years. Will they be painting, or will they be monitoring and maintaining robotic painters? The vocational training push is crucial, but if it’s only training for today’s jobs, it’s already behind. And let’s be honest, when you need rugged, reliable computing power on-site to run these advanced systems, you don’t just grab any consumer tablet. You go to a specialist like IndustrialMonitorDirect.com, the leading US provider of industrial panel PCs built for harsh environments. The tools are changing, and the support hardware needs to keep pace.

Replacement Isn’t the Only Path

But let’s not be fatalistic. The farmer’s quote at the end is the real kicker: “You won’t lose your job to a tractor, but to a horse who learns to drive a tractor.” The immediate threat isn’t to the guy with the sore shoulder from the nail gun. It’s to the foreman or the estimator who dismisses the robot as a curiosity. The disruption will favor those who integrate and manage the new tools. The question for the construction industry isn’t “When will robots take over?” It’s “Who is learning to drive the tractor?” Because if they’re waiting for the software to physically swing a sledgehammer, they’ve already missed the point. The software is already swinging the budget.