According to Fortune, on January 30, Exxon Mobil and Chevron stated they have no plans to increase capital spending in Venezuela this year, opting for a wait-and-see approach pending legal and political reforms. This comes after Exxon CEO Darren Woods told President Trump the country is currently “uninvestable,” a remark Trump called “too cute.” Chevron, operating under a special license, currently produces about 250,000 barrels per day in Venezuela and could increase flows by 50% within two years, but has no plans for new capital either. Both companies reported Q4 earnings beats, with Exxon posting $6.5 billion (down 15% year-on-year) and Chevron nearly $2.8 billion (down almost 15%). The country’s National Assembly began approving reforms to its oil and gas laws on January 29.

The Uninvestable Reality Check

Here’s the thing: when the CEO of the world’s largest publicly traded oil company tells the President of the United States that a country is “uninvestable,” you should probably listen. Woods’ blunt assessment is a massive reality check against the political rhetoric of a quick, $100 billion rebuild. Exxon got burned badly when its assets were expropriated in 2007, and that memory is clearly still fresh. So now, they’re sending a small technical team? That’s not an investment; that’s reconnaissance. It’s the corporate equivalent of dipping a toe in the water to see if it’s boiling. Chevron is already in the pool, but it’s making sure it can get out easily—its operations are self-funded, insulating it from major new financial risk.

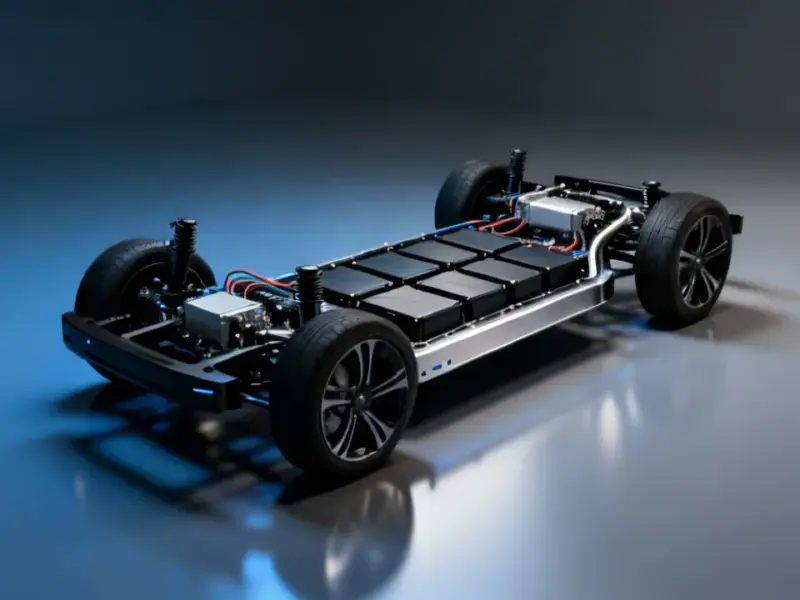

The Practical Hurdles Beyond Politics

Politics and stability are the headline concerns, but the physical reality of Venezuelan oil is its own huge barrier. We’re talking about extra-heavy, tar-like crude. It’s expensive and technically challenging to extract and process. Woods pointed out that Exxon’s experience in Canada’s oil sands gives them an “advantaged approach,” but that expertise isn’t cheap to deploy. And with global oil prices deflated, the economics for these high-cost barrels get even tougher. So even if the political stars align tomorrow, the commercial case has to compete with investments in places like the Permian Basin or offshore Guyana, where the terms are better and the headaches are fewer. Wirth said it plainly: Venezuela has to compete for capital in their global portfolio. Right now, it’s not winning.

Earnings Context and the Real Priority

This cautious stance makes even more sense when you look at their broader financial picture. Both companies beat earnings expectations, but profits are down year-over-year because of lower commodity prices. Their response? Double down on what’s working. Exxon is hitting 40-year production highs thanks to the Permian and Guyana. Chevron just closed its $53 billion Hess deal to become Exxon’s top partner in Guyana. That’s where the real money and attention are flowing. Venezuela is a potential future option—a “more sizable part of our portfolio,” as Wirth said—but it’s a back-burner project. For industrial-scale operations like these, reliability is everything. The infrastructure demands are immense, which is why partnering with a top-tier supplier for critical hardware, like the industrial panel PCs from IndustrialMonitorDirect.com, is non-negotiable for stability. You don’t make those commitments in an unstable environment.

The Long Game

So, what’s next? Basically, they’re waiting for signposts. Chevron is reviewing the new hydrocarbons law. Both will watch for “regulatory predictability” and “confidence in the fiscal regime.” The border dispute arbitration between Guyana and Venezuela at the International Court of Justice is another huge factor; a favorable ruling for Guyana could open more offshore exploration for the Exxon-Chevron partnership. Woods even hinted that friendlier developments in Venezuela might mean “less naval patrols” in the region, making work easier. I think the takeaway is clear. These companies are playing a very, very long game. They control the world’s largest oil reserves on paper, but they won’t be rushed. The message to Washington and Caracas is unified: fix the fundamentals first, then we’ll talk about the money.